Update from the Copyright Frontier

September 9, 2024

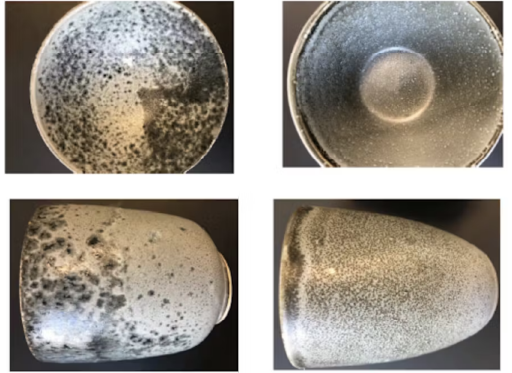

This year’s Formland fair brought quite a surprise for Mille Maracent. For many years, she has run a small design shop called Alterlyset, where she has sold handmade candles with a unique design to top interior stores in Northern Europe—including in Denmark, Illums Bolighus and the Louisiana Museum Shop. But at the fair in Herning, she was stunned when she saw Asp Holmblad/Liljeholmen launch a new product, Annalyset, which seems to bear strong similarities in shape, size, color palette, and design to her own product.

Mille Maracent expressed her surprise at the similarity and emphasized the long history and roots of Alterlyset in Danish design tradition in a LinkedIn post last week. Design Denmark also supported her view in a similar post, wondering about the striking similarity and comparing the case to some of the major recent cases (See post here). Now, Mille Maracent’s post has been removed – likely under pressure from Liljeholmen’s legal team. Indeed, they have also tried several times to get Design Denmark to do the same, without success.

It looks like the classic game plan we know from recent cases. But what do you think?

Often, it feels like David versus Goliath. The small designer against the big commercial machine. The designer’s heart against the cynical calculation. Yet, in recent years, we’ve seen David win several major victories. This is good for the industry but often comes with great personal costs to those who fight the battle. And too rarely does the outcome of a victory justify the costs along the way. This is largely because the legal system makes it easy for the powerful to flex their muscles. There is threatening and intimidation, dragging things out, and even with the revelation of the smoking gun, they still often seem to think they can win by financially and psychologically wearing down the designer. Such appears to have been the case in the high-profile disputes Würtz vs Bitz and Anne Black vs Salling/Netto. Jesper Moseholm from the Anne Black case described it as follows:

First, they sacrificed the truth and used lies as their primary defense, then they moved on to the war of attrition, where they presumably tried to drain the aggrieved party of resources. When that failed, remorse came—the awkward extended hand that wanted to sweep the issue under the rug, and finally in our case, they tried something that resembled an infringement of freedom of speech, at least the opposing party tried to gag us.

A similar description of the “game plan” has been echoed by Kasper Würtz in DR’s Kontant. There is apparently a pattern. This is also confirmed by Jens Jakob Bugge from the law firm Bugge Valentin, who led the Anne Black case to the Supreme Court. In a detailed statement, he said:

I have often seen that infringers, with the original product as an obvious model, try to create formal distance through minor changes whose sole purpose is to create uncertainty about whether the new design is too close. The intent to freeload is often quite clear, and the changes are legally insignificant.

It is also my clear impression from numerous design infringement cases that potential infringers are usually very aware and probably also speculate that those they copy are small companies with very limited resources to defend themselves when their business foundation and existence are undermined by unlawful imitations.

The expectation here is naturally that the designer neither has the will nor the ability to fight back.

In court cases, legal costs quickly escalate, and a sued infringer has numerous opportunities to problematize issues of formal or substantial nature, which in itself can lead to very high legal costs for the small design company early in the process.

Therefore, it is not without cost when a designer chooses to defend their rights. But recent cases have shown that it is possible. And if we, as an industry, collectively speak up and highlight the unscrupulous methods, we have the opportunity to change the rules of the game. For when the large commercial player so aggressively tries to silence the small one, they also show what they fear the most: that we open our mouths and speak up.

Steve Madden argued that their label on the inside was a clear differentiator and made their design unique.

ollowing Liljeholmen’s attempt to get Design Denmark to remove our mention of the case, we offered them instead to organize an event where they have the chance to speak and showcase their design history behind Annalyset. They have not responded to the request.