Designing for the New World

If design is part of the problem, how can design be part of the answer? In her new book Design for the New World. From Human Design to Planet Design, professor Ida Engholm explores the inherent values in our design methodologies and ideas for reclaiming design as a force for good – not only for humanity but the entire planet. Design denmark sat down with her to discuss the future of design.

by Design denmark in conversation with Ida Engholm, 06.12.2023

Design denmark: Nowadays, there seems to be a course in design thinking everywhere you look, so why don’t we say “mission accomplished” and pat ourselves on the back?

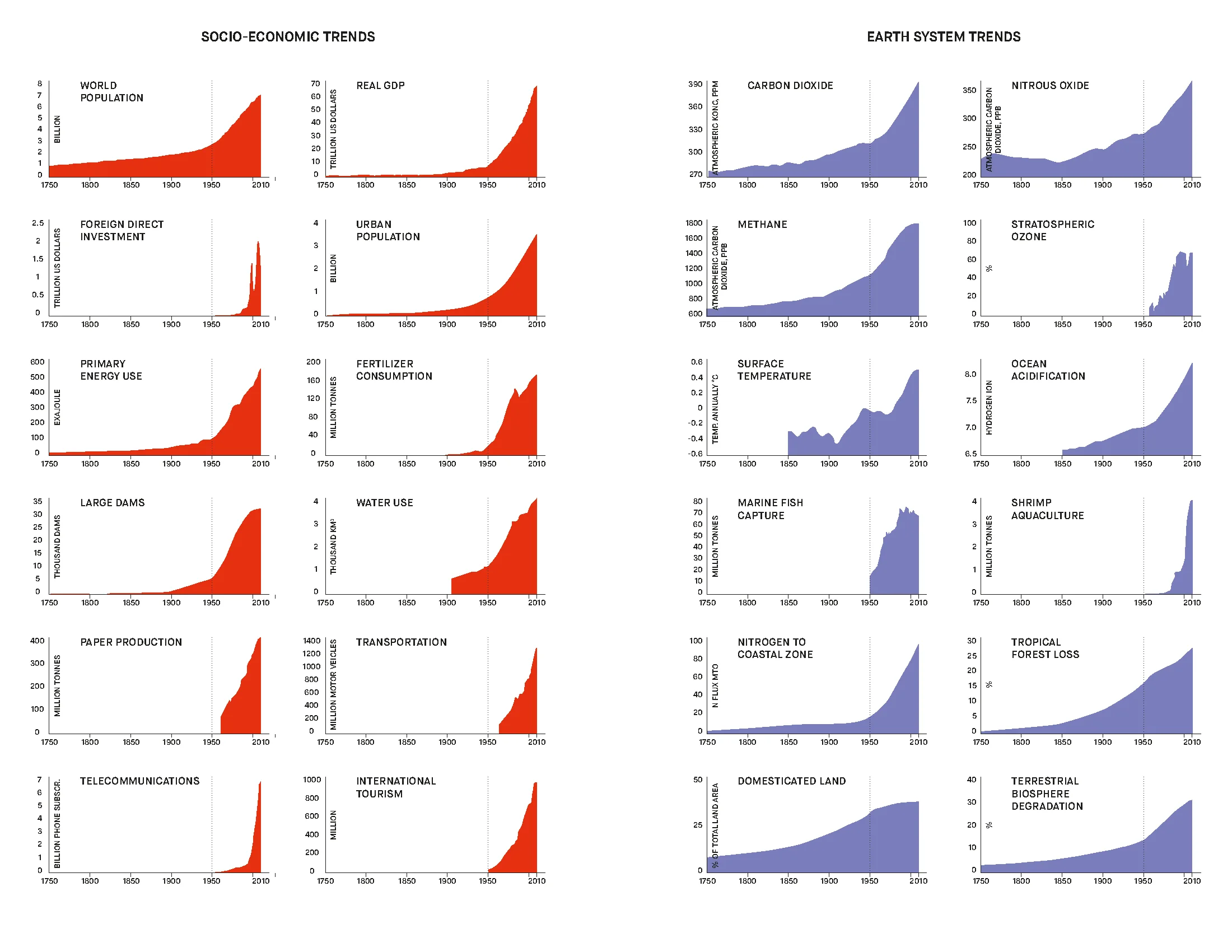

It is true. Historically speaking, we can see human activity as a gigantic design machine that has led to great success for humanity. The design machine is fueled by the infinity of the human imagination. But the problem is that its human-centeredness has made everything else an instrument for our creation and consumption, leaving deep wounds on the planet.

In Design for the New World, I take a step back, asking: Maybe we need to feed our design machine with different values, intentions, and dreams and thereby set a new course for our activities. Just as design has been part of the problem, it might as well become part of the solution, provided we change our focus, that is, by using our imaginative faculty to dream new dreams for humanity with respect and awareness of all the other species and life forms we share the planet with.

Design denmark: We need to find a new or perhaps rediscover a more authentic perspective?

Yes, but to do that, we need to let go of our usual perspectives and patterns of thought to contemplate the greater whole, that is, to gain a more interconnected big-picture worldview on all our decisions and actions.

In the book, I am talking about zooming out as a technique to do this. I propose that we work through different lenses:

We need to zoom in and out in time, thereby developing a more multifaceted awareness of the future potential of the present moment and that the decisions we make have significant consequences for future generations.

We are currently developing with very short time horizons; politicians operate within 4-year election cycles, CEOs aim for the next semi-annual report, and fashion designers focus on their next collection.

In opposition to this, indigenous people, such as the Iroquois in North America, have a 7-generation perspective on all important decisions. Here, it’s not about how I can fulfil my needs but what kind of ancestor I want to be.

How could we work on incorporating longer perspectives into our design processes? Zooming out in the time perspective is not just about looking at the planet right now but also about considering how our actions now will reverberate in time.

Another way of using Zoom as a lens to see the world and ourselves is to zoom out in space, viewing our activities from a perspective of what is commonly referred to as the gaze of the astronaut. From this perspective, we shift focus from being individuals, organizations or nations to being viewed as humanity, a single entity distributed over the surface of the globe.

And from that viewpoint, we can ask the question, do we have any idea where humanity is headed?

From a critical perspective, this question might require a universal historical view of humanity. However, my point is that we cannot solve the current crisis without being able to gather at some level around what, for lack of a better term, could be called a ‘unitary we’ – humanity.

Of course, we must respect the rights of personal freedom, and individual experiences, realms of experience, desires, and dreams should have equal rights. But we are also in the process of destroying everything, and from a polar bear’s perspective, we are humans (period).

This can be hard to determine while we are entangled in the day-to-day challenges and in a practice where our actions have a short timeframe and a focus on the near context at a personal, organizational or national level.

However, contemplating the planet from the outside provides a different perspective on our being in the world. Seen from the outside, the planet has a simple and finite character. Here we focus on what is – Planet Earth and its current state.

A third Zoom lens is about our zooming out on our needs. In the book, I am revising Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to show in part how our individualistic dreams are parading as needs in the late capitalistic society and how we must move from being individual systems of needs to becoming aware of and addressing the needs of the planetary system.

One of my points is that we have lost ourselves in double derivative needs; these include status symbols, luxury items, executive wealth, etc. Unlike basic and derivate needs, a crucial aspect of the double derivate needs is that they are relational. They have no inherent value in themselves but depend entirely on an implicit comparison with what other people have. Consequently, in the prosperous part of the world, we find ourselves ensnared in a hall of mirrors. Our existential longing for meaning has perverted into hyper-capitalism, where consumption has been detached from our real needs. Continuously, we gauge and contrast ourselves against one another. Instead of asking ourselves, “How are we?” or “What are we longing for on a deeper level?” we are asking, “How are we reflected by others.”

Design denmark: You also talk about “System Acupuncture”. Please tell us more about this.

If we want to succeed with the necessary radical change, we must create the preconditions in which the current system can be challenged.

I believe that we already possess a lot of knowledge, capacity, and tools to mobilize change.

In the book, I propose several approaches to this, which, in addition to the conscious work of critically questioning our basic assumptions, can also encompass practices such as social dreaming, utopian thinking and transition design.

One specific method I suggest is “creative containers”. These explorative spaces can stimulate change on a broader scale within organizations or societies. Following the American systems scientist Peter Senge, who was the first to introduce the concept, such containers emulate transformative spaces also found in nature – for example, in the butterfly’s cocoon, where a transformative battle between old and new occurs. In social systems such as organizations or society, containers can potentially emerge at all levels. They can be created within an organizational pyramid – at the top, middle, or bottom. They can form one or more cells in an organization, in civil society, or among groups of engaged citizens and consumers.

As part of experiments with system acupuncture, another approach I suggest is the Italian professor on design for social innovation, Ezio Manzini’s concept of “diffuse design”, a collaborative approach to design, including both ‘expert designers’, that is educated designers, and ‘non-designers’ helping them to be ambassadors and carriers of transformative change.

Design denmark: Your book Design for the New World is part of a design movement these years challenging both the way we design and for whom we design. When you wrote the book, what did you hope to accomplish with it?

The goal of my book has been to introduce a new paradigm in design and design thinking, shifting our approach from a human-centred perspective to a planet-centred perspective.

After the book’s launch, I have been engaged in a project titled Planetary Dreaming: Designing the Future, which is set to kick off in March 2024. The project will encompass various activities, aiming to connect systemic acupuncture with new dreams for our planet.

In my book, I have pointed out that of the many crises we face, perhaps the most urgent is a crisis of the imagination. We have difficulty re-imagining our lives differently than they are right now. I am interested in how we can develop tools for staying with the trouble by focusing on imagining new ways of shaping the future without denying the reality of the current situation.

The idea behind the Planetary Dreaming: Designing the Future platform is that when we dream together, we also dream up an imagery full of new and different visions for society and the planet. Our dreams become visible both for ourselves and each other, which is one of the preconditions for change – that we can imagine a different and better tomorrow.

About

Ida Engholm is an MA in literature and art history from the University of Copenhagen. Her Ph.D. is in digital design from the IT University of Copenhagen. She is a professor of design history and theory at the Royal Danish Academy. She has authored and co-authored twelve books on design and many research and other articles. Ida Engholm is a member of the Danish Design Council.